For nearly 30 years, federal financial aid was off-limits to people in prison. The 1994 Crime Bill stripped incarcerated individuals of access to Pell Grants - the same federal aid that helps millions of low-income students pay for college. The result? College programs in prisons nearly vanished. By 2004, participation had dropped by half. But in December 2020, Congress changed course. It restored Pell Grant eligibility for all incarcerated people, with full implementation starting July 1, 2023. Today, more than 800,000 people in U.S. prisons are eligible for federal aid to pursue degrees, certificates, and diplomas. And for the first time in decades, higher education is making a real comeback behind bars.

Why Pell Grants Matter in Prison

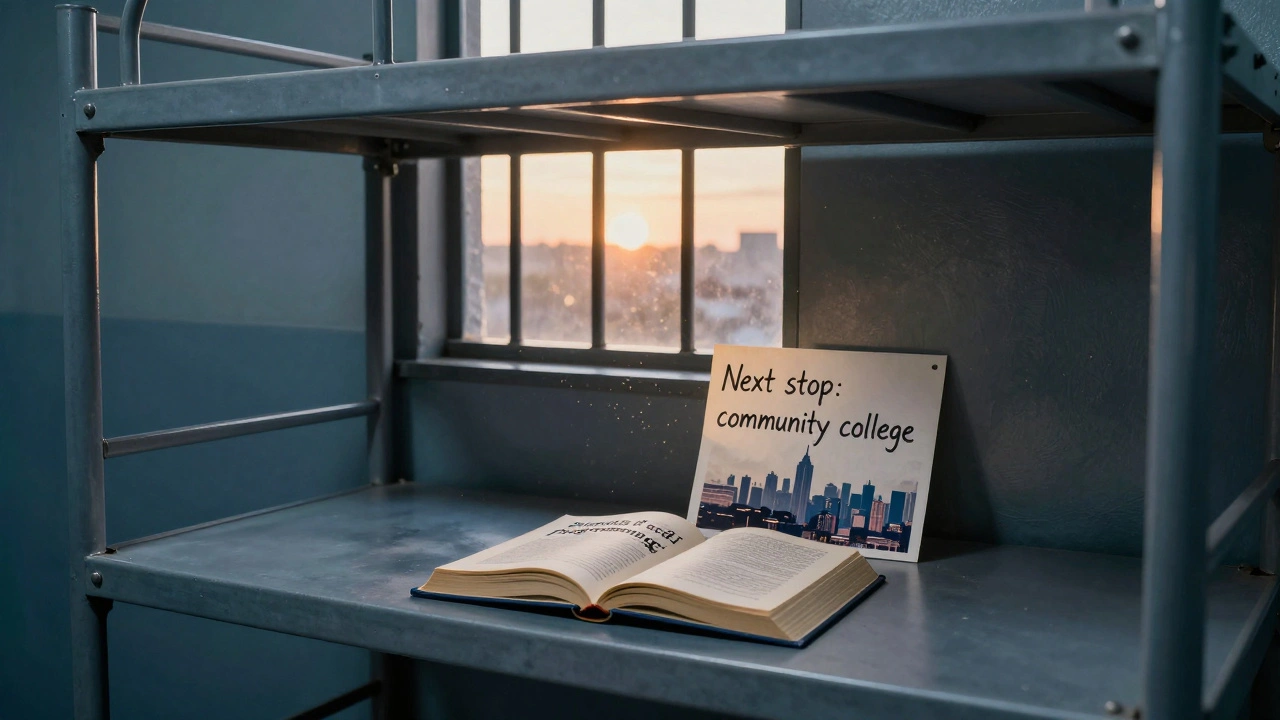

Pell Grants aren’t just about tuition. They’re about dignity. They’re about giving people a real shot at rebuilding their lives after release. Before the ban, prison education programs were thriving. In the early 1990s, over 350 colleges offered courses in prisons. By 2014, that number had shrunk to fewer than 100. The 1994 ban didn’t just cut funding - it sent a message: education doesn’t belong in prison. That message is now being undone.With Pell Grants back, colleges are stepping in. Over 200 institutions - from community colleges to private universities - now offer classes in correctional facilities. In Kansas, all eight state prisons have college programs. In Arkansas, six colleges work together to bring courses into all 17 state prisons. California enrolls over 10,500 students per semester. These aren’t isolated efforts. They’re part of a nationwide shift.

Who’s Enrolling - and Who’s Not

More than 70% of people in prison say they want to go to college. But actual enrollment is still low. In 24 states, fewer than 5% of eligible and interested individuals are enrolled. In another 16, it’s only between 5% and 9%. Why? Because access isn’t just about money - it’s about infrastructure.At two-year colleges, Pell Grants cover nearly all enrolled students - 94% in one study. At four-year schools, Pell recipients make up just over half. That gap tells us something important: community colleges are leading the charge. They’re flexible, affordable, and focused on practical skills. A certificate in welding, a two-year associate degree in business - these are the programs that are working. They’re not just about theory. They’re about jobs.

But here’s the problem: many prisons still lack basic resources. Libraries are outdated or locked. Online learning tools don’t work because prison internet is restricted. Academic advising? Often nonexistent. A Vera Institute report found that nearly half of all states rated as “inadequate” for academic and career advising. You can’t just hand someone a textbook and expect them to succeed. You need mentors, counselors, and clear pathways.

The Real Impact: Recidivism Drops

The most compelling reason to fund college in prison? It works. People who take college courses while incarcerated are 48% less likely to return to prison. That’s not a guess. It’s backed by decades of research. One study tracked people for five years after release. Those who earned a degree had a recidivism rate of just 13%. Those who didn’t? 44%.This isn’t just about reducing crime. It’s about saving money. The average cost of housing one person in prison is over $40,000 a year. A college education costs a fraction of that - and pays off long-term. Every degree earned means one less person cycling back into the system. That’s not charity. It’s smart policy.

Who’s Getting Left Behind

Not everyone benefits equally. Early data shows that white men enrolled in technical certificate programs were the most likely to receive Pell Grants in the pilot phase. That doesn’t mean others aren’t interested - it means access isn’t fair. Black and Latino incarcerated individuals, who make up the majority of the prison population, are still underrepresented in these programs.Why? Because program placement isn’t random. Colleges tend to partner with prisons that have space, staff, and political support. Rural prisons? Often overlooked. Women’s prisons? Under-resourced. Juvenile facilities? Almost never included. And then there’s the post-release gap. Many programs stop at the prison gate. No help finding a college in the community. No guidance on financial aid for continuing education. No connections to employers. Without that bridge, degrees sit unused.

Where Programs Are Working

Some states are getting it right. Utah and Washington scored “adequate” on all five quality metrics used by the Vera Institute: credit transfers, credential pathways, program availability, advising, and research access. Kansas built a statewide network of colleges working together. Arkansas created a consortium so no prison is left without options.At one community college in Maryland, a student earned an associate degree in criminal justice while serving time. After release, he got a job with a nonprofit that helps formerly incarcerated people find housing. He’s now studying for his bachelor’s degree online. That’s the kind of story that proves this works.

At another institution in Ohio, a former inmate completed a certificate in computer programming. He now runs a coding bootcamp for people leaving prison. He didn’t get there because of luck. He got there because someone gave him a chance - and the tools to use it.

The Gaps That Still Exist

Even with Pell Grants restored, big problems remain. Technology access is still limited. Most prisons don’t allow internet access, so online courses are hard to deliver. Some schools use paper-based learning. Others rely on limited tablet systems with preloaded content. That’s not college. It’s a workaround.And what happens after release? Very few programs offer transition support. A person might earn an associate degree in prison, but if they can’t find a college that accepts their credits, or if they’re denied financial aid because of their record, that degree becomes a wall - not a ladder.

Libraries are another issue. Many prisons have no access to academic journals, research databases, or even updated textbooks. How can someone write a research paper without Google Scholar? How can they learn if the only resource is a 20-year-old copy of a biology textbook?

What Needs to Change

To make this work at scale, we need three things:- Stronger student services - academic advising, tutoring, career counseling - built into every program.

- Post-release pathways - partnerships with community colleges, scholarships for formerly incarcerated students, and employer pipelines.

- Better technology access - secure, monitored digital learning platforms that allow for real-time interaction and research.

States that treat prison education as a public service - not a privilege - are seeing results. New York, Washington, and Oregon have started pilot programs that follow students after release. They connect them with local colleges, help them apply for aid, and even offer housing support. These aren’t just nice ideas. They’re necessary.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t about forgiving crime. It’s about breaking cycles. People in prison aren’t a lost cause. They’re parents, siblings, neighbors. Many were never given a real chance before they ended up behind bars. A college education doesn’t erase the past. But it gives people something to build - not just a future, but a reason to stay out.When we invest in education behind bars, we’re not just helping individuals. We’re making communities safer, stronger, and more just. The data doesn’t lie. The stories don’t lie. And the numbers - 48% fewer returns to prison - speak louder than any policy debate.

The work isn’t done. Enrollment is still too low. Support is still too thin. But the door is open. And for the first time in decades, higher education is no longer a privilege behind bars - it’s a possibility.

Are Pell Grants available to all incarcerated people now?

Yes. As of July 1, 2023, all individuals incarcerated in federal or state prisons are eligible for Pell Grants. This includes people in state prisons, federal prisons, and juvenile detention centers. No one is excluded based on the nature of their offense, sentence length, or location.

How many people in prison are actually enrolled in college programs?

While over 800,000 people in prison are eligible for Pell Grants, actual enrollment is still low. In many states, fewer than 5% of eligible and interested individuals are enrolled. Even in states with strong programs like California or Kansas, enrollment typically reaches only 10-15% of the eligible population. Barriers like lack of advising, limited course offerings, and poor access to materials keep numbers down.

Do college programs in prison reduce recidivism?

Yes - and the evidence is strong. Studies show that incarcerated individuals who participate in college programs are 48% less likely to return to prison. One long-term study found that those who earned a degree had a recidivism rate of 13%, compared to 44% for those who didn’t participate. The impact is even stronger for those who complete associate degrees or vocational certificates.

What types of degrees are most common in prison?

Associate degrees and career certificates are the most common. Programs in business, criminal justice, computer skills, welding, and medical assisting are popular because they lead directly to jobs after release. Bachelor’s degrees are offered, but completion rates are lower - partly because they take longer and require more support. Two-year colleges have the highest success rates because they’re focused on practical, timely outcomes.

Why aren’t more prisons offering college programs?

It’s not a lack of interest - it’s a lack of infrastructure. Many prisons lack space, staff, or funding for academic services. Some don’t have reliable internet, libraries, or computers. Others have rules that limit outside instructors or require expensive security for classes. Political will also varies. Some state corrections departments still see education as a luxury, not a necessity. Without state investment and clear policy, progress stalls.

Can someone continue college after release?

Yes - but it’s not easy. Pell Grants are still available after release, but many formerly incarcerated people face barriers: lack of documentation, credit transfer issues, or being denied financial aid due to past convictions. Some states and nonprofits are creating bridge programs to help with applications, housing, and enrollment. But nationwide, support after release is inconsistent and often missing.