When someone is locked up, changing how they think is often harder than changing their behavior. You can take away a weapon, enforce a curfew, or assign chores-but thoughts? Those live inside a person’s head. That’s why prison-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) focuses on cognitive restructuring: the slow, deliberate process of replacing criminal thinking patterns with healthier ones. But how do you know if it’s working? You can’t just ask someone if they feel better. You need hard data. And that data is being collected, analyzed, and used to reshape how correctional systems deliver therapy.

What Exactly Is Cognitive Restructuring in Prison?

Cognitive restructuring isn’t about making inmates nicer. It’s about fixing the hidden wiring that leads to crime. Think of it like this: most people who commit offenses don’t wake up one day and decide to rob a store. They’ve been thinking for years that rules don’t apply to them, that violence solves problems, that victims deserve it, or that they have no control over their choices. These aren’t just bad habits-they’re deeply rooted thought patterns called criminal thinking.

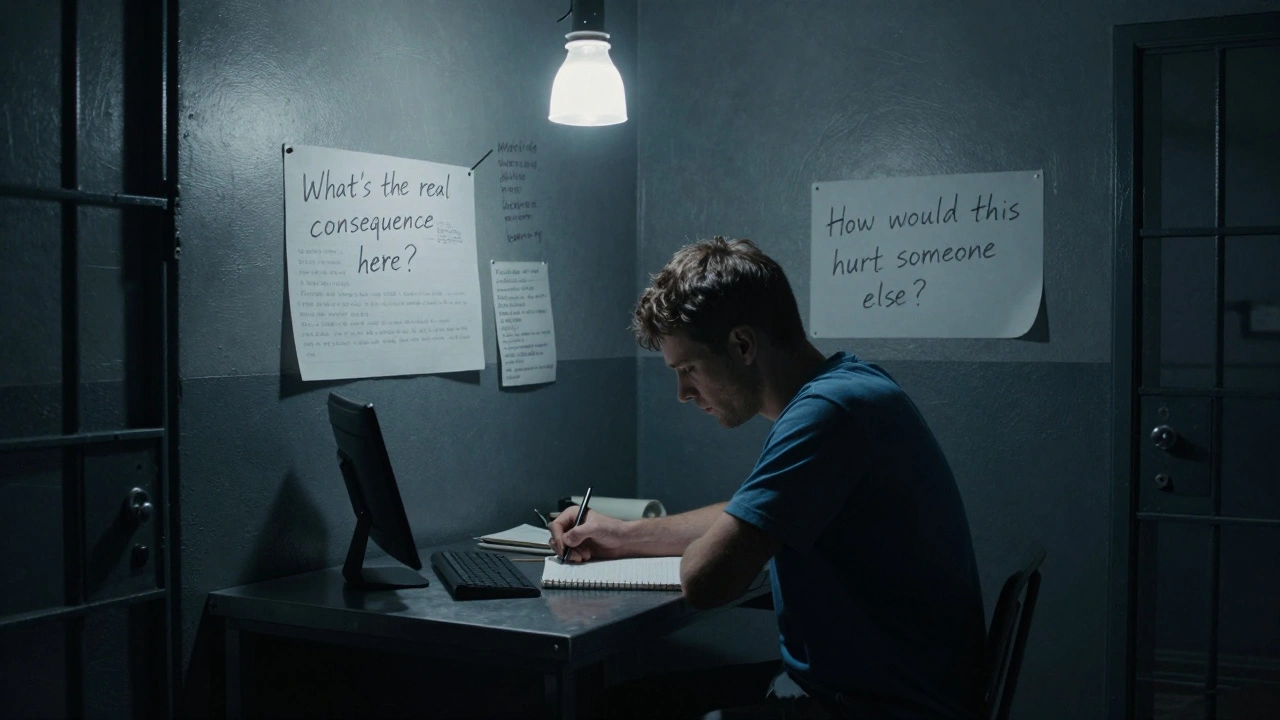

Prison CBT programs target these patterns head-on. Using structured exercises, group discussions, and workbook activities, inmates learn to recognize when they’re slipping into old thinking. For example, instead of reacting to a slight with aggression, they’re taught to pause and ask: "What’s the real consequence here?" or "How would this hurt someone else?" These aren’t abstract ideas. They’re practiced daily, like learning a new language.

How Do You Measure a Thought?

You can’t see a thought. But you can measure its effects. The most reliable tool used in federal and state prisons is the Texas Christian University (TCU) Criminal Thinking Scales. It’s not a personality test. It’s a validated survey that breaks criminal thinking into specific, measurable domains:

- Superoptimism - Believing you won’t get caught

- Power Orientation - Thinking dominance equals respect

- Criminal Rationalization - Justifying illegal behavior

- Victim Empathy Deficit - Not seeing harm done to others

- Impulse Control - Acting without thinking ahead

Before a program starts, inmates take the TCU survey. After completion, they take it again. The difference? That’s your gain. Research from the University of Cincinnati’s Thinking Things Through (TTT) program showed that participants dropped significantly on impulse control and victim empathy scores. But not everywhere. Some areas, like superoptimism, didn’t shift as much. That’s critical. It means cognitive restructuring doesn’t work the same way for everyone. You have to measure each piece.

What Happens After the Therapy?

Measuring change inside prison is one thing. But does it last? That’s the real test. Studies tracked participants for up to a year after release. The results were clear: inmates who completed intensive CBT programs had a 25% lower rate of rearrest compared to those who didn’t. That’s not a small number. It means for every four people who would have gone back to prison, one didn’t-because their thinking changed.

But here’s the twist: misconduct inside prison often went up during the first few weeks of CBT. Why? Because when you start challenging someone’s core beliefs, they get defensive. They act out. They test boundaries. It’s not failure-it’s part of the process. That’s why long-term tracking matters. If you only look at short-term behavior, you might think the program is making things worse. But if you wait six months? The drop in disciplinary reports is sharp and steady.

What Makes a Program Work?

Not all CBT programs are built the same. The ones that actually move the needle on cognitive restructuring have three things in common:

- Intensity - At least two hours, three times a week. Programs that meet less often show little to no change.

- Fidelity - Staff follow the exact curriculum. No skipping modules. No improvising. Even the best program fails if it’s poorly delivered.

- Reinforcement - New thinking is practiced in real time. If an inmate has a conflict, staff don’t just punish them. They ask: "What thought led to that?" and guide them through the right response.

California’s 14-week program and the federal 120-day Corrective Intervention Pre-Release Program both use workbook-based exercises combined with digital assessments. Inmates complete daily "thinking reports" after incidents. These aren’t just logs-they’re data points. Each report gets coded for which cognitive skill was triggered, whether it was applied correctly, and how it affected the outcome. Over time, this builds a personal profile of change.

The Role of Risk and Responsivity

One-size-fits-all doesn’t work in prison therapy. The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model says you need to match the program to the person. High-risk offenders need longer, more frequent sessions. Low-risk ones might benefit from a shorter version. But more importantly, the program has to match how they learn.

Some inmates respond better to written exercises. Others need role-playing. Some need one-on-one coaching. Programs that adapt to individual learning styles see higher completion rates and deeper cognitive gains. The READI program in Chicago tried paying participants $25 per session to attend CBT. It worked at first-55% signed up. But after a few months, attendance dropped. Why? Money didn’t change thinking. Only consistent practice did.

What About Youth?

Cook County’s Juvenile Temporary Detention Center took a different approach. Instead of waiting for a survey, they tracked thinking in real time. Every time a teen got into trouble, they filled out a "thinking report" right after: "What were you thinking right before you acted?" "What did you expect to happen?" "What did you wish had happened?"

By 2017, this real-time feedback loop cut juvenile readmissions by 16 percentage points. For every 1.4 kids who went through the program, one avoided returning. That’s not just data-it’s lives. And it proves that measuring cognitive restructuring doesn’t always require fancy surveys. Sometimes, it just needs someone asking the right question at the right moment.

Why This Matters Beyond Prison Walls

Changing how someone thinks behind bars doesn’t just reduce crime. It changes families. It changes communities. It changes the cost of incarceration. The U.S. spends over $80 billion a year on prisons. Every person who doesn’t return to prison saves taxpayers tens of thousands of dollars. But more than that-it gives people a chance to rebuild.

Cognitive restructuring isn’t magic. It’s work. Hard, repetitive, sometimes frustrating work. But when it’s done right-with good tools, trained staff, and honest measurement-it changes outcomes. And that’s the only thing that matters.

Can cognitive restructuring be measured without surveys?

Yes. While standardized tools like the TCU Criminal Thinking Scales are the gold standard, behavioral observation is also powerful. Programs like Cook County’s use real-time "thinking reports" filled out after incidents. These capture the actual thought process behind behavior, giving immediate feedback on whether restructuring is happening. Over time, patterns emerge: fewer impulsive reactions, more consideration of consequences, better emotional regulation. These are measurable gains-even without a paper survey.

Do all inmates benefit equally from CBT?

No. Research shows high-risk offenders with strong criminal thinking patterns benefit the most-but only if the program is intensive and well-delivered. Low-risk individuals may not need the same level of intervention. Also, some inmates struggle with trauma, substance use, or mental illness that blocks cognitive change. Programs that screen for these issues and adjust delivery (like adding trauma-informed support) see better results. One size doesn’t fit all.

How long does it take to see cognitive restructuring gains?

Initial shifts can appear in as little as 4-6 weeks, especially in impulse control and emotional awareness. But meaningful, lasting change usually takes 3-6 months of consistent participation. The TTT program showed significant gains after 12 weeks of daily sessions. The key is duration and frequency-short, sporadic programs rarely work. Think of it like learning to play piano: a few lessons won’t make you fluent. You need daily practice.

What’s the difference between cognitive restructuring and general therapy in prison?

General therapy might focus on feelings, past trauma, or coping with isolation. Cognitive restructuring is laser-focused on changing specific criminal thought patterns. It doesn’t ask, "How do you feel?" It asks, "What were you thinking right before you broke the rule?" and then walks the person through a better alternative. It’s practical, targeted, and behavior-driven-not just emotional.

Are prison CBT programs effective outside the U.S.?

Yes. Studies in the UK, Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands show similar results. The core principles of cognitive restructuring-identifying distorted thinking, practicing alternatives, reinforcing new patterns-are universal. The tools might vary slightly, but the outcome doesn’t: consistent, well-implemented CBT reduces recidivism by 20-30% across different justice systems.

What’s Next?

Prisons are slowly moving from punishment to rehabilitation. But progress isn’t automatic. It depends on who’s running the programs, how they’re funded, and whether leaders care enough to measure what matters. Cognitive restructuring isn’t about making inmates feel good. It’s about making them think differently-and that’s something you can count, track, and prove.