When someone in prison wants to sue over mistreatment, poor conditions, or denial of medical care, they can't just walk into court and file a lawsuit. There's a rule they must follow first: exhaust all administrative remedies. This isn't a suggestion. It's a legal requirement written into federal law - the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) of 1996. Skip this step, and your case gets thrown out before a judge even looks at it.

What the PLRA Actually Says

The PLRA is clear: "No action shall be brought with respect to prison conditions... until such administrative remedies as are available are exhausted." That means if you're in a prison, jail, or detention center, and you want to sue under federal law - whether it's for excessive force, inadequate medical care, or unconstitutional living conditions - you have to go through the prison's own internal complaint system first. No exceptions. No shortcuts. Even if the prison staff ignored your complaint or refused to help, you still have to go through the motions.

The Supreme Court made this crystal clear in Ross v. Blake (2016). Judges can't make exceptions, even if it seems fair. If the prison has a grievance system, you must use it. Period. The idea isn't to punish inmates - it's to give prisons a chance to fix problems before courts get involved. Courts don't want to waste time on issues that could be solved internally.

What Counts as an "Available" Remedy?

Not every complaint system is real. Some prisons have rules on paper that don't work in practice. The Supreme Court says: if the system is a dead end, it's not "available." For example, if you file a grievance and the staff throw it out without reviewing it, or if the rules say you can appeal but no one ever accepts appeals, then you don't have to exhaust that path. It's not your fault the system doesn't work.

But here's the catch: if the prison says you can appeal, and you just don't bother - even if you think it's pointless - you lose. The court doesn't care if you thought it was a waste of time. You have to follow the steps. Even if the remedy can't give you money (most prison grievance systems can't), you still have to go through it. The PLRA doesn't care whether the remedy gives you the relief you want. It only cares whether the process existed.

How to Actually Exhaust Remedies

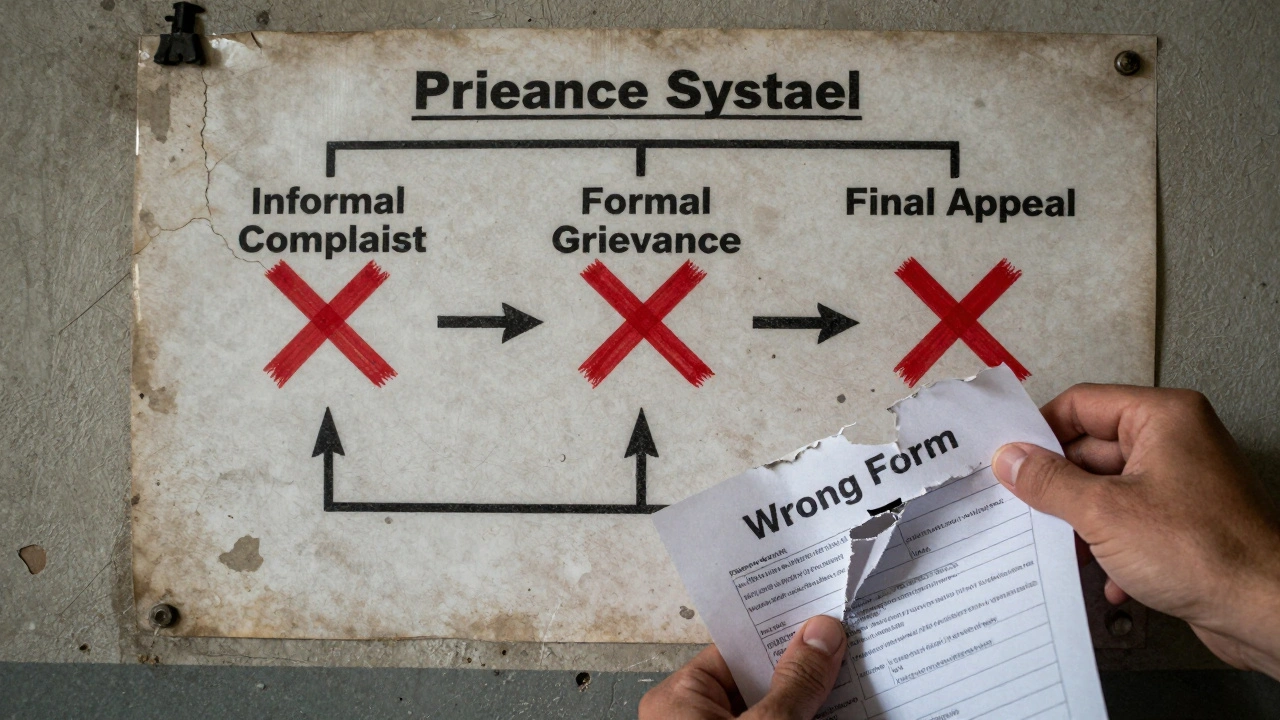

Every prison has its own rules. Some use a three-step system: informal complaint, formal grievance, then appeal. Others use two. Some require specific forms. Some require hand-delivery. Some require you to submit within 15 days. Miss a deadline? Skip a step? Use the wrong form? Your claim is dead.

You must follow the exact procedure laid out in the prison’s handbook. That means:

- Using the correct form (not a letter, not a sticky note)

- Filing at the right time (within the deadline)

- Submitting to the right person (not just handing it to a guard)

- Appealing at every level if required

There’s no "good faith" exception. If you file on day 16 instead of day 15, you lose. If you forget to sign your appeal, you lose. If you don’t name the guard who hurt you in the grievance, you might lose your right to sue them later. Courts have ruled that you must identify the person you’re complaining about in the grievance - otherwise, the prison system can’t investigate them.

What Happens in Court? The Burden of Proof

Here’s the part most inmates don’t know: you don’t have to prove you exhausted remedies when you file your lawsuit. That’s not your job. The burden falls on the prison officials. They have to raise the issue and prove you didn’t follow the rules.

This changed in 2007 with Jones v. Bock. Before that, judges would dismiss cases if the inmate didn’t mention exhaustion in their complaint. Now, that’s not required. You can file your lawsuit saying, "I was beaten by Officer Smith." The prison has to respond later, saying, "No, you didn’t file a grievance about it." Then they have to show proof - maybe a copy of the grievance log showing no record of your complaint.

That means you can still get your case heard even if you messed up the process - if the prison doesn’t catch it early. But don’t count on it. Most correctional systems now train their lawyers to look for exhaustion failures. If you skipped a step, they’ll find it.

Common Mistakes That Kill Cases

Here are real-world mistakes that get cases thrown out:

- Filing a grievance about "poor food" but not mentioning the specific guard who denied your medication

- Waiting three weeks to file because "I didn’t know the rules"

- Handing a complaint to a guard who says, "I’ll give it to someone," and never following up

- Not appealing after the first denial - even if you think it’s pointless

- Using the wrong form number or writing on the back of a receipt

One case from Oregon involved an inmate who wrote a letter to the warden about being denied psychiatric care. He didn’t use the official form. He didn’t file it through the grievance system. When he sued, the court dismissed it. The prison had a clear system. He just didn’t use it.

When Can You Skip Exhaustion?

There are only a few narrow exceptions:

- Unavailability: The system doesn’t work - no one responds, no appeals are accepted, or the rules are impossible to follow.

- Futility: The prison has a history of ignoring complaints on this issue. (Note: This is rare. Courts rarely accept "futility" alone.)

- Emergency: If you’re in immediate danger and can’t wait for the process (e.g., you’re being attacked daily and the prison refuses to intervene).

But again - courts are strict. If the prison has a written procedure, even if it’s broken, you usually still have to use it. The law doesn’t let judges make exceptions based on fairness.

Why This Matters

The PLRA exhaustion rule isn’t just paperwork. It’s a wall. Every year, hundreds of valid claims get thrown out because inmates didn’t follow the rules. Many don’t even know the rules exist. Others try to use the system, but get lost in the bureaucracy. Guards don’t always explain it. Legal aid is scarce. And once you miss a step, you can’t go back.

For prisons, this rule works. It reduces lawsuits. For inmates, it’s a trap - unless you know how to navigate it.

What You Should Do

If you’re in prison and considering legal action:

- Get a copy of the prison’s official grievance policy. Ask the law library or a counselor.

- Write down every incident - dates, names, witnesses, what happened.

- File your grievance immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s "not important enough."

- Follow every step. Appeal every denial. Keep copies of everything.

- Don’t rely on verbal promises. Only written records count.

- If you’re denied, write a note: "I am appealing this denial under Section 3 of the grievance policy."

Even if you think the system is broken - use it anyway. It’s your only legal path forward. If you don’t, you lose your right to sue - no matter how serious the abuse.

Do I need to name the specific guard in my grievance to sue them later?

Yes. Courts have ruled that if you don’t identify the person you’re accusing in your grievance, you can’t sue them later. The prison needs to know who to investigate. If you write, "a guard beat me," but don’t say who, you can’t name Officer Smith in court. Be specific.

Can I file a lawsuit if I didn’t finish all appeal steps?

No. You must complete every level of appeal required by the prison’s rules. If the policy says three steps, you need three. Skipping one - even if you think it’s unnecessary - means you didn’t exhaust. Courts won’t excuse you.

What if the prison lost my grievance?

If you can prove you filed it - through a copy, witness, or mail receipt - and the prison has no record, you may have a case. But you must show the grievance was properly submitted and that the prison failed to process it. Courts will still expect you to have tried.

Can I sue if I’m still in prison?

Yes. The PLRA doesn’t require you to be released before suing. You can file while incarcerated. But you still must exhaust administrative remedies first.

What if the prison doesn’t have a grievance system?

If a prison has no formal grievance process at all, then there’s nothing to exhaust. In that rare case, you can go straight to court. But most states require prisons to have one. If they claim they have one but you can’t find it, ask for a copy in writing - and keep the request as proof.